|

Results from the most recent round of studies examining tillage options for corn production are in. Corn growers can use the information to balance soil protection issues with crop productivity and fuel costconcerns to arrive at the best options for individual operations. |

Recent research undertaken by the University

of Guelph was designed to assess corn yield response to a range of tillage

systems. In particular, this round of experiments continued to examine tillage

systems that attempted to improve on the 'no-till' condition. These techniques

maintain the majority of the crop residue and the benefits of reduced tillage,

but at the same time attempt to reduce the risks (due to high soil density,

slow soil warming, etc.) of the no-till system.

Reduced

tillage approaches

Reduced

tillage approaches

One of the more obvious options for enhancing corn yields in reduced tillage

systems is to do some loosening deeper into the soil profile. This can be

done without disrupting much of the crop residue on the soil surface and can

be confined to zones where next year's corn rows will be planted. This approach

was implemented at the University of Guelph research sites in the Granton

and Ridgetown research locations. Deep loosening was accomplished in the fall

prior to corn production to a depth of 35 cm (14 inches) on some plots using

a deep ripper. Fall zone tillage using the Trans-till was also employed with

an operating depth of 15 cm (6 inches). Corn was planted the following spring

over top of these loosened zones without any further tillage.

Tandem discing of either wheat or soybean stubble has been used to incorporate residue and do some shallow soil disturbance in the fall. This approach was employed on all of the sites in this study as well. In all cases, this treatment, referred to as 'Fall Disk Only' was planted directly without any spring tillage.

Researchers

also compared two no-till planter configurations in this study, one where

a three coulter configuration was used on the front of the planter, and one

where the three coulters were lifted out of the way leaving only the single

disc fertilizer opener and spoked row cleaners in advance of the seed opener.

Researchers

also compared two no-till planter configurations in this study, one where

a three coulter configuration was used on the front of the planter, and one

where the three coulters were lifted out of the way leaving only the single

disc fertilizer opener and spoked row cleaners in advance of the seed opener.

Corn Yields

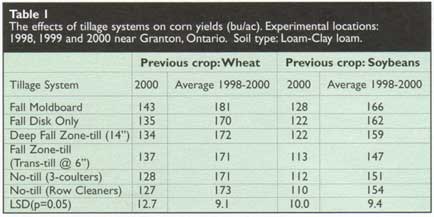

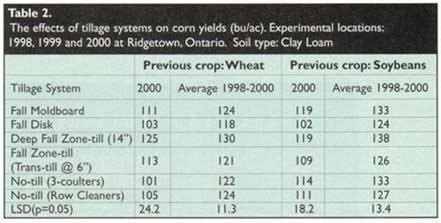

Tables 1 and 2 outline the corn yields from several tillage systems being

compared at these sites over the last three years. The first thing to notice

is that deep loosening in the row zone appeared to have little impact on yields.

(No positive impact at Granton, some higher yields at Ridgetown but not statistically

significant). This despite the fact that penetrometer numbers showed soil

profiles that were significantly less resistant than in the no-till plots.

The shallow fall discing generally produced yields that were no better than

no-till.

Some of the most significant benefits to fall strip tillage or discing may have less to do with soil loosening and more to do with creating an in-row area that will be more suitable for planting, perhaps earlier than no-till. This benefit is hard to quantify, however, as all plots were planted on the same day in these studies.

The other interesting observation is how well

reduced tillage performed on wheat stubble at these sites. Traditionally,

no-till corn after wheat has been considerably tougher to manage than no-till

following soybeans. However, it appears that increasing success rates following

wheat relate more to moisture and temperature management than to soil density;

tile drainage and straw removal both seem more important than extra tillage

operations.

Conclusions

Further analysis of reduced tillage and strip tillage options will continue

to be done using the data from these sites and from other strip tillage projects

currently underway. One thing apparent from this project, is that there were

few advantages to intermediate forms of tillage in terms of corn yields. Doing

a good job of no-tilling, (accurate starter fertilizer placement, in-row residue

removal, and good seed-to-soil contact) yielded as well as all other systems

except moldboard plowing.

No doubt some will look at these yield results and say that it proves moldboard plowing is still the way to grow corn. From a maximum yield perspective, that point is hard to argue with. However, as fuel prices increase, you must look at bottom line profitability. Compare your costs for moldboard plowing and spring cultivating to no-tilling and spraying a burn-down herbicide. If you take six bushels off the moldboard yields to allow for these additional costs, the no-till option comes out looking quite reasonable in most situations. And that is with no credit to the no-till system for prevention of soil erosion, building soil organic matter, or offering superior traffic-bearing capacity in the fall.

The crunch between low corn prices and rising

energy costs will be dramatic in 2001. Reduced tillage for corn, although

with its limitations on poorly drained soils, or where manure management is

required, continues to offer options worth considering.

Acknowledgements

All data presented in this article is courtesy of T. Vyn, Purdue University,

K. Janovicek, B. Deen, D. Young, University of Guelph. Researchers express

gratitude to farm co-operators in the Granton area: J. Scott, S. Malcolm,

J. Hodgins and B. McIntosh, and to OCPA and CanAdapt for funding this work.